As I was folding my laundry tonight, I was thinking about everything that’s happened over the past few days, at the national level, but more importantly what was going around me in my local city. And some things aren’t adding up.

(As I’m writing this, President Trump has just declared a national emergency over the spread of COVID-19, aka the Coronavirus. It’s been only a few days since major sporting events were suspended and cancelled, most notably the NBA and March Madness. So I don’t know right now how things are going to play out over the next few weeks or months.)

Over a decade and a half ago, I used to be a manufacturing engineer in the automotive industry. One of my regular duties was to conduct something called an FMEA, Failure Modes Effects and Analysis. It was a risk assessment over what could possibly go wrong in a car (or a component of it), which guided what type of preventive measures and quality checks had to happen.

The Big Three automakers had a pretty standard system: there were three measures, rated on a scale from 1 to 10. You multiply the three numbers to get anything between 1 and 1 thousand. The bigger the number, the bigger the risk. If it was something under a hundred, you almost didn’t think about. However, if it was close to a thousand, it was all hands-on-deck, the-company-could-go-out-of-business bad.

These were the three measures: severity (what’s the worst case), occurrence (how often does it happen), and detection (how quickly can it be spotted).

I’m going to add in a fourth factor to the calculation: contagion. The automotive FMEA doesn’t account for this, because when a tire blows out on one Ford Explorer, it doesn’t cause three or four other Explorers to crash. So now our scale goes from one to ten thousand.

In thinking about the virus, I decided to apply my FMEA math. So let’s go:

(Disclaimer, I’m going to throw out some numbers, but all of these are second-hand with no references. This is a thought experiment, not a policy paper.)

Severity

OK, people are dying, so this is pretty high, at least a 5. But how high? In my mind, a 10 would be a practical death sentence: over 80% mortality rate. Get your affairs in order, you’ve got less than a month to live.

Right now, the highest mortality rate is something like 14 to 18 percent among the elderly. For middle-aged people it’s in the single digits, and for those under 35, it’s less than half a percent. So pretty survivable.

I’d give it a 7.

Occurrence

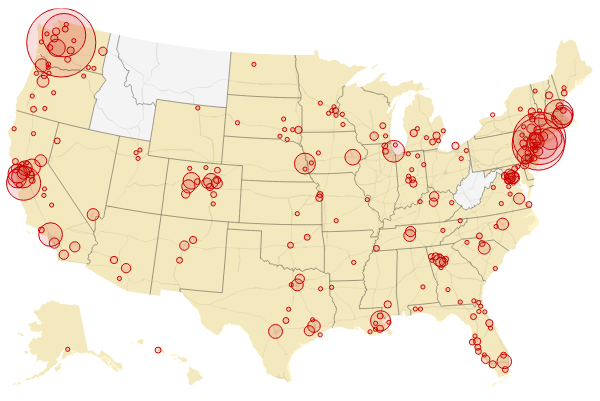

So right now there are over 400 cases in the United States, out of a population of 330 million. While all but two states have at least one case, a lot of them are concentrated in three specific regions: the Seattle region, the San Francisco Bay, and the Atlantic corridor between Boston and DC. King and Snohomish Counties in Seattle account for more than 3/4ths of all cases, which means that outside of Seattle, it’s pretty rare.

I’m going to give this a 2. (3 if you’re in Seattle.)

Detection

OK, this one’s gonna be pretty big. By all accounts, it could take as long as two weeks before symptoms show up, and a patient could still infect others in the fortnight while it’s incubating. Automatic 10 here.

(Note that I’m leaving out testing, or the lack of it so far. That’s part of the quality control plan, and a rant for another day.)

Contagion

This one’s a little bit hard to estimate, because the scale is a little vague. By all accounts, the virus is fluid-borne, not airborne like the common cold. In the air it lasts like 2 to 3 minutes, but on a surface it could last 2 to 3 days. So contagious, but not so contagious that you catch it simply by being in the same room.

(Again, not talking about preventative measures like washing hands or disinfecting surfaces. Talking risk assessment, not quality control.)

I’m going to call it a 6.

Assessment

So let’s run the numbers: 7 x 2 x 10 x 6 = 840.

That’s a little higher than I thought. However, on the scale of 10 thousand (10 x 10 x 10 x 10), it comes out to a ratio of around 0.084.

Bad but manageable.

Now, I’m not saying that the President is wrong to call a national emergency, or that major decision makers are overreacting by postponing or canceling events. They have way more skin in the game than I.

But for the average Joe on the street, it’s slightly worse than surviving a natural disaster. And when you think about it, just about every part of North America has to prepare for some kind of a disaster: blizzards in the north, hurricanes on the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, tornadoes in the Midwest, wildfires in the west, and earthquakes on the Pacific Coast.

Mother Nature loves to mess with us Americans.

I think we’ll be OK. Slightly worse for the wear, but generally OK.